Do you know what you focus on most when watching a dance or choreographing? And how would you answer the question: What is fundamental to dance? Is it possible to create choreography without knowing the answer to this basic question?

Sure. But it will most likely be a creation that will copy familiar formulas and practices. If a choreographer wants to get beyond these, he/she needs to know what the dance actually consists of. I fully agree that dance is a poetic language, but I also believe that the choreographer/performer needs a more analytical view of dance. In this blog I will try to explain how this affects the understanding of choreographic creation.

WHAT FORMS FOUNDATION OF DANCE?

Every art form has defined elements that form its foundation. In music, for example, melody, rhythm, harmony, dynamics, and color are considered the basic elements; in visual arts, these are most often point, line, shape, form, color, shade, texture, and space (or proportion).

From the above, it is obvious that dance shares several “resonant surfaces” with both music and visual arts. Often dance works are also distinctive visual or musical achievements. But does dance have its own defined elements? Why is this important?

Dance is a visual art that takes place in space and at the same time (like music) in time. Space and time are therefore necessarily essential elements of dance. However, the primary element of dance is undoubtedly the body. It is a very different type of instrument from the musical instrument or the tools of the painter or sculptor. The body is the living source of dance. There is no gap between the dancer and the dance – the dancer is the dance that is happening.

The body expresses itself with its own language of movement that can be read. Its dynamic qualities have as strong an effect on us when we observe dance as its shape (visual) aspect. Dance thus deals with the same elements as visual and musical art but brings its own perspective.

A FEW DEFINITIONS

The American modern dance choreographer Doris Humphrey, in her publication Art of Making Dances, defined the four elements of dance as follows: design in space, dynamics, rhythm and motivation. Humphrey explains:

“Every movement made by a human meaning […] has a design in space; a relationship to other objects in both time and space, an energy flow, which we will call dynamics; and a rhythm. Movements are made for a complete array of reasons involuntary or voluntary, physical, psychical, emotional, or instinctive – which we will lump all together and call motivation. Without a motivation, no movement would be made at all. So, with a simple analysis of movement in general, we are provided with the basis for dance, which is movement brought to the point of fine art. The four elements of dance movement are, therefore, design, dynamics, rhythm, and motivation.” (D. Humphrey: The Art of Making Dances, 1997, P. 46)

In Dance Composition – A practical guide for teachers, British educator, and author Jacqueline M. Smith-Autard lists the components of dance composition as: the dancer’s body, movement, space, and relationship. (J. Smith-Autard: Dance Composition – A practical guide for teachers, 1992, p. 38)

I also posed the question of what the elements of dance are to another source of information we already have. The GPT Chat on August 5, 2023, gave me the following answer: body movement, rhythm, music, space, time, force/intensity, gesture and expression, choreography, costumes and props, cultural and historical context, balance and alignment, coordination and control, partnering and interaction, improvisation.

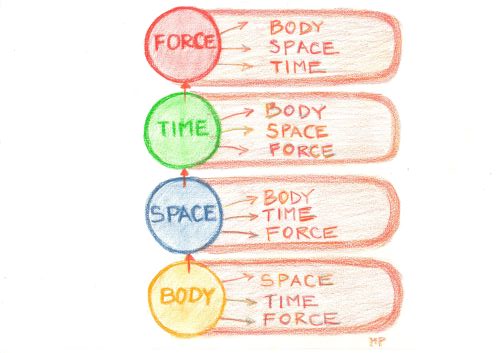

There are several points of view, but for me the simplest concept, set by Rudolf Laban as a basic framework for analyzing movement (not only dance movement, but any movement of the human body), has proved to be the most useful in practice. Although Laban Movement Analysis uses more specific concepts, it basically operates with four elements of movement: body, space, time and force.

In this context, another question arises: What is the difference between dance and movement? The simple answer would be not all movement is dance, but all dance is movement. Thus, there are two frames, the smaller of which (dance) is part of the larger (movement). Movement is an essential activity of a living organism. Dance is a specific movement with certain qualities.

The most common definition of dance is: dance is a rhythmic movement of the body performed to the accompaniment of music. At the beginning of the 20th century, when representatives of modern European dance began to experiment with dancing in silence (Rudolf Laban, Mary Wigman and others), the definition of dance was narrowed down to rhythmic-dynamic movement. In the second half of the 20th century, American postmodern dance brought about another redefinition: dance is any movement that is included in the context of dance. Choreographers centered around the Judson Dance Theatre project (Yvonne Rainer, Trisha Brown, Steve Paxton, and many others) focused on everyday movement in their search for a new dance expression, preferring the non-dancing body (a body untrained by the practice of familiar dance techniques) as a source of inspiration. In their performances from the 1960s, dance movement was often not even present. These experiments had a profound influence on the further development of dance and choreography. They undoubtedly broadened the conception of dance as an art form, but at the same time orientation in it became more difficult.

In this respect, too, Laban’s categorization is advantageous in its clarity and simplicity as a tool for distinguishing the basic elements of movement. Laban also called them components of movement. Since they act simultaneously, our mind perceives them comprehensively when observing movement. However, when choreographing, it is essential to perceive them individually and work with them in detail.

When creating, I personally see them as “layers” of movement – each providing a distinctive quality to the dance. It is important to understand how they work individually, but also to understand their interplay in their interrelationships. Therefore, it is not only about analysis (breaking down the movement into its individual elements), but then also about their integration. The interrelationships of the components of movement operate on certain logical but often unpredictable and surprising principles that have an infinite number of manifestations.

If we do not work with well-known movement vocabularies when creating choreography but create our own movement material (I wrote about movement material in this blog), it is difficult – if at all possible – to compose all movement elements at once. Why is that?

Movement is an extremely complex experience, and our minds are not able to keep track of all the layers going on at once – it inevitably misses something, even in less complex movements. This is probably due to the fact that our mind combines all the components of a movement at once into a complex experience in order to be able to evaluate them more quickly. That’s why I see them as “layers” and focus my attention preferentially on composing a particular “layer” at different stages of the creative process.

Creating a choreography is a process of fine-tuning all the “layers”, and a change in one of them changes the whole, which could actually happen endlessly. The skills of a choreographer therefore include the ability to decide when this process is complete. It is only acquired through practice.

TENDENCY AND FOCUS

When I work with students or look at the choreography of other artists, another fact fascinates me – each person tends to perceive some elements of the dance more strongly than others. This is also experienced by the audience, when several people watch a dance, they notice different qualities in the dancers’ movement.

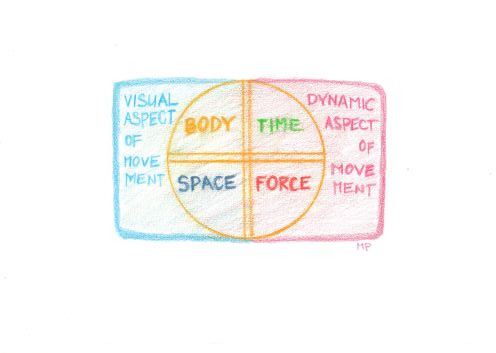

Detecting one’s own tendency in the perception of movement is also aided by another framework that allows one to understand how the choreographer processes sensory information. Although we get all information about dance visually, yet we each perceive two aspects of dance differently: the visual and the dynamic (I also call it energetic).

Finding out where my tendency is going, and which aspect or element of movement I most often focus my attention on, is key information. Based on it, I can also address those aspects and elements that mostly remain in the shadows of my attention, and so I can develop my compositional skills more comprehensively.

It takes practice to incorporate an analytical perspective into dance making. It provides an opportunity to develop multiple skills beyond the ability to compose a dance form. It is obvious that the individual elements of dance (and especially the relationships between them) also manifest meaning-making. Analytical skills allow choreographers to clarify what qualities of the movement components most interestingly capture the idea they wish to communicate through dance.

Developing these skills opens up a richer perspective on dance as an expressive language for dancers and choreographers, but most importantly, it allows us to more easily break away from the established movement patterns that our bodies and/or our minds are quick to offer us as ready-made solutions in the process of creation.

GAINING CLARITY AND CONFIDENCE IN THE CREATIVE PROCESS

Developing choreographic skills requires a lot of experimentation where the choreographer develops an understanding of what and how works and makes sense to him/her in the dance. This is a long-term process of gaining experience, which is the basis for being able to make quicker and more appropriate decisions about how to proceed in the creative process. An analytical framework allows the choreographer to process more effectively the information he/she gains from observing and thinking about compositional tools and practices, and thus develop the skills to articulate more clearly his/her creative intentions (what I am doing and how I am doing it). Clearer articulation then helps to develop greater confidence in making creative decisions, as well as presenting the results of the work.

How do I perceive the individual elements?

The body – a somatic approach to movement that focuses on the perception of the body in its full breadth of different systems and levels (anatomical, physiological, psychological, etc.) is for me an absolute essential when working with the body/movement/dance, as it significantly expands the possibilities of embodying choreographic ideas. This approach also includes sensitivity to the individuality of the body of each dancer I work with.

Space – although I have a natural inclination towards the perception of space, it took me some time to understand the amazing possibilities dance has to make space visible. According to Laban, space is a potential for movement. I am fascinated by how the dancing body can “charge” space with its energy, as long as dancer consciously works with it. I consider working with space to be one of the primary structural components that “holds” the choreography together.

Time – I perceive it in choreography in terms of two levels: lived (subjective) and chronological (objective) time. I mainly focus on living time allowing for the feeling of movement, to which I also adapt the choice of music so that it does not limit the movement too much with its structure. It is very important for me that the dancer feels his/her body in movement from the inside – then s/he can create interesting rhythms that either interact with the music in an interesting way or are fully capable of filling the silence.

Force – I understand this element in close relation to the body – only a functionally tuned body can work with different intensities of force in a way that is appealing and authentic. Modeling strength in movement is another essential key to dance expressiveness for me. I have noticed that the way different choreographers handle the element of force in movement is often significant to their choreographic style.

In conclusion, I will emphasize once again that analysis is the phase of the process where I focus my attention only on a particular aspect of the movement, and then integrate the information in clear detail so that the movement achieves a quality that embodies the idea that I want to communicate through dance.

CHOREOGRAPHIC SKETCH – VIDEO

The video demonstration for this blog is also a little test to see how you can focus your attention on just one of the elements of movement. The basis of the demonstration is a short dance phrase that is repeated, with each repetition focusing your attention on the selected element of movement. In the same way, the dancer focuses her attention on a particular element to make it more visible.

What to notice when focusing attention on observing the body: what actions the body does, how its shape changes moment by moment, which parts of the body lead the movement in each action.

What to notice when focusing attention on observing spatial qualities of movement: changes in the direction of movement, transitions through levels of space, what paths in space the dancer draws as she moves through space.

What to notice when focusing attention on observing the temporal properties of movement: how movement unfolds in the flow of time, when it speeds up, when it slows down, when and for how long it stops, what rhythmic patterns emerge in the movement.

What to notice when focusing attention on observing the transformations of force in movement: how the dancer models muscular intensity, when the movement is vigorous and when it softens, inflates, or swings.

You may also notice that by focusing attention on a particular element, the overall quality or “atmosphere” of the dance phrase has changed. What makes them different for you? Which element were you able to read most easily in the movement? Can you imagine how you could use this knowledge when creating choreography? When you look back at the way you choreograph, which element do you focus on the most (which do you spend the most time on)?

NOTE: I originally created the diagrams in this blog on the computer, but then decided to draw them by hand, because the color gradients allow me to visualize that the verbal categories that help us mentally understand complex phenomena can never quite capture their boundlessness – the elements of motion simply intermingle in each moment.

Dear readers, if you would like to share your thoughts and experiences on this topic with me, I would be very happy. Thanks for your reactions J.

Marta